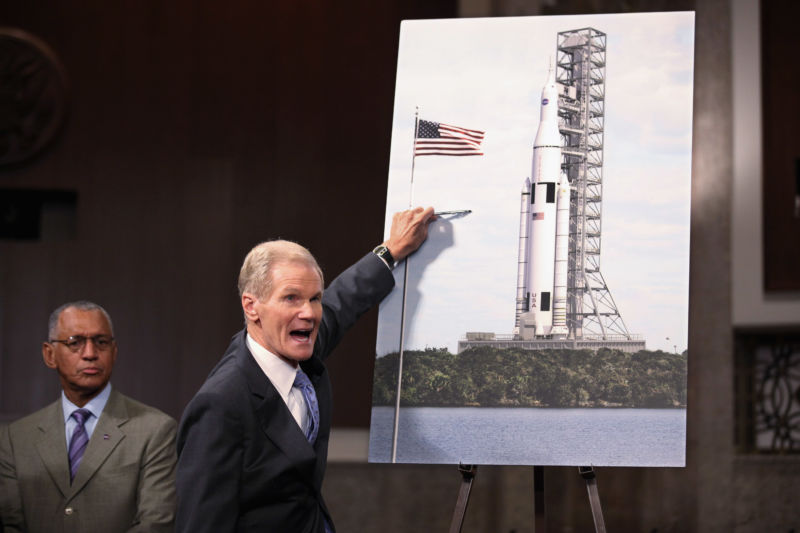

Why do you want this job? —”If we can’t do a rocket for $11.5 billion, we ought to close up shop.”

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

This morning, the White House nominated former US Sen. Bill Nelson to become the next administrator of NASA.

Nelson, who is 78 years old, lost his 2018 bid for reelection to the Senate. He had served six terms as a member of the House of Representatives and three terms in the upper house. He has a close relationship with President Biden and effectively lobbied to gain the appointment. Nelson must still be confirmed by a majority of the US Senate, but this seems likely to happen given early support from some Republicans already.

“Most every piece of space and science law has had his imprint, including passing the landmark NASA bill of 2010 along with Senator Kay Bailey Hutchinson,” the nomination states.

The former senator, who did indeed delve deeply into space policy, would bring plenty of experience and familiarity to the role of NASA administrator. In addition to representing Kennedy Space Center in Congress for decades, he flew as a payload specialist on space shuttle Columbia in January 1986. However, Nelson is far from beloved in the space community, both for the way he became an astronaut and for some of his space policy decisions.

Only senators get to ask questions of nominees at hearings, but if Ars had a seat at the table, here are the top five questions we’d be most interested in hearing Nelson respond to.

1. If commercial space can do a better job, should NASA buy in?

Nelson was initially antagonistic toward commercial spaceflight—particularly efforts to rely on private companies to deliver astronauts to the US space station. For example, during a Senate hearing in 2010, he suggested that the Senate might simply take President Obama’s $6 billion request for commercial crew funding and put that money into the Space Launch System rocket.

“What would happen if Congress decided—since the Congress controls the purse strings—that we wanted to take the $6 billion projected by the president over the next five years and use that not for human certification of the commercial vehicles but instead to accelerate the … heavy-lift vehicle for the Mars program?” Nelson asked during one hearing.

Nelson made similar comments over the course of several years. He ultimately started making more positive comments about commercial crew after Boeing established in 2014 that its facility to process the Starliner crew vehicle would be at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Later, he also began to appreciate that SpaceX would launch dozens of times a year from Florida. This makes clear that Nelson’s motivations lie in protecting jobs in Florida—a parochial, if understandable, motivation for a senator from the state.

But a NASA administrator must represent all of NASA, not just stand up for a few states. Today, it’s fairly well-established that NASA should buy commercial services from private companies in low Earth orbit. The debate now is whether this public-private partnership model should be extended into deep space for exploration. Doing so would likely save money and accelerate exploration, but it also threatens parochial political interests in Alabama, Florida, and elsewhere. Would Nelson be willing to stand against former friends in the Senate and aerospace industry to accomplish this?

2. Do you still believe politicians should not run NASA?

In 2017, Nelson led the opposition to Jim Bridenstine becoming administrator of NASA. Then serving as the ranking member on the Senate’s Committee on Commerce, Science, & Transportation, which oversees NASA, Nelson said Bridenstine was too partisan and political to lead NASA. He also accused Bridenstine of not having the expertise to do so. “The head of NASA ought to be a space professional, not a politician,” Nelson said of Bridenstine, then a two-term congressman from Oklahoma.

Now Nelson, a former politician like Bridenstine, will find himself in the witness chair. Why should the rules he used to oppose Bridenstine four years ago not apply to him now?

3. How can NASA grow the nation’s global climate leadership?

During the Bridenstine confirmation process in 2017, Nelson also accused Bridenstine of being a climate-change denier. In response, Bridenstine replied that his views on the subject had evolved, and true to his word, he generally supported NASA’s efforts to study Earth science during his tenure.

One concern scientists have expressed about Nelson is that his support for Earth science was lukewarm during his tenure in the Senate. Yes, he absolutely believed in climate change and recognized the threat. However, he was far more interested in finding funding within the NASA budget for the Space Launch System rocket, and particularly hundreds of millions of dollars a year for work on ground systems at Kennedy Space Center.

The Biden administration has identified climate change as a top threat the United States must confront. How would Nelson attack that subject? And how would he work with the president’s science advisers to do so?

4. Should NASA close up shop?

Alongside Texas Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, in 2010 and 2011, Nelson was a key architect of the SLS rocket. NASA and the White House were wary of tackling this project, as it was well understood that building the rocket through traditional, cost-plus contracting methods would be time-consuming and expensive. The Obama administration wanted to see if private companies, such as United Launch Alliance and SpaceX, could do a better job.

Nelson relentlessly fought against this and promised that the SLS rocket program would deliver. “This rocket is coming in at the cost of what not only what we estimated in the NASA Authorization act, but less,” Nelson said at the time. “The cost of the rocket over a five- to six-year period in the NASA authorization bill was to be no more than $11.5 billion. This costs $10 billion for the rocket.”

Later, he went further, saying, “If we can’t do a rocket for $11.5 billion, we ought to close up shop.”

More than a decade later, and having spent more than $20 billion, NASA is still probably about a year away from launching the SLS rocket for the first time. Despite notching a successful test firing on Thursday, the program has been panned by critics as a “jobs program” that is hampering NASA rather than advancing its interests.

So should NASA close up shop? Or more realistically, should NASA accede to what the Obama administration wanted to do a decade ago and acknowledge that the private sector does a much better job of building rockets than government institutions?

5. Why do you want this job?

It’s not clear what Nelson’s vision for NASA is, and this is important, because serving as administrator is a difficult and demanding job. Frankly, there is widespread skepticism in the space community about Nelson’s motivations. His flight on space shuttle Columbia in 1986 was widely seen as an opportunistic move to advance his political career. Some of his fellow astronauts nicknamed him “Ballast” for the role they perceived he played during the mission.

Bridenstine’s nomination, of course, was also met with widespread skepticism in 2017, and he generally overcame those concerns to get high marks from space historians. It’s possible that Nelson could rise to the occasion as well, and certainly the space community will be rooting for him to lead NASA forward. But how would he do that?

Back in 2017, some of us who track space policy closely understood that Bridenstine brought a lot to the table. During his two-plus terms in the House of Representatives, Bridenstine had shown a keen interest in space policy, and not for parochial interests. He was genuinely interested in seeing the US spaceflight enterprise—across civil, commercial, and national defense domains—advance into the future. He spoke of lunar resources as America’s Sputnik moment in space and authored the ambitious American Space Renaissance Act. He wanted the NASA job to begin making those reforms, and that’s what he tried to do.

Now, it’s not clear why Nelson wants this job. What are his passions? How will the 78-year-old push NASA into a new era when the space industry is rapidly changing, with the emergence of myriad commercial companies and the rise of Chinese competition in civil space? Hopefully he can articulate this and explain how he will help get NASA astronauts to the Moon this decade, to stay, and in a sustainable way.

By Eric Berger