On the first day of Christmas —

Santa falls into an ambiguous category between “real” and “nonreal” for many children

Jennifer Ouellette

–

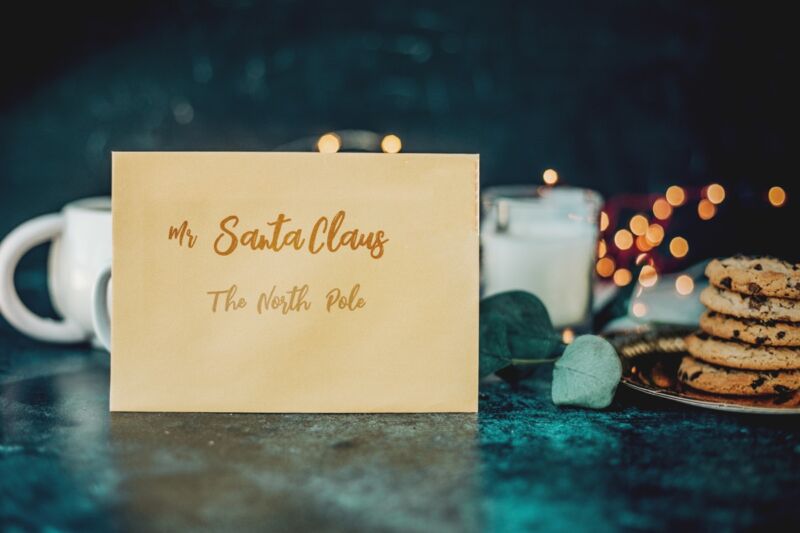

Enlarge / Writing letters to Santa Claus and leaving out milk and cookies are two actions that reinforce children’s belief.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2020, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: how children’s belief in Santa Claus is part of a hierarchical pantheon of real and non-real figures.

Do you believe in Santa Claus? If you’re over the age of eight, you probably don’t. We tend to think young children are simply more gullible due to their tender years. But their belief in Santa, the Tooth Fairy, or similar cultural figures isn’t quite as simple as that, according to a June paper published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Rather, such figures fall into an ambiguous category between “real” and “nonreal” for many children, indicating that their belief structures are much more nuanced than previously believed. Rituals like writing letters to Santa, or leaving out milk and cookies on Christmas eve, reinforce their belief in these ambiguous figures. The fact that the milk and cookies are gone on Christmas morning serves as a form of indirect evidence, and when children interact with a Santa figure at the mall, it further reinforces that belief.

“[Children] are cannier than we give them credit for.”

“Historically, in the field of psychology, it was held for a long time that children are gullible, which is very unfair,” lead author Rohan Kapitany of Keene University told Ars. “They ask a lot of questions. They think deeply. Children do believe in these things at much higher rates than adults, but you can’t just convince them that the boogeyman is under the bed. It’s a lot harder than that. They are cannier than we give them credit for.”

Kapitany earned his PhD in developmental psychology, focusing on how children learn through imitation, and this led to his interest in the role of ritual in shaping beliefs. He was interested in exploring further how children evaluate different types of figures across a spectrum of real and non-real.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that [rituals] are so often linked to religions and invisible things like values and beliefs, and it seems like very fertile soil to begin to understand how children reconcile reality,” he said. “Santa and the Easter Bunny are easy examples, but children have to grapple with more complex things, like dinosaurs, or the presence of a contagion in our world. We don’t get direct evidence of it, and so we look to people’s behaviors to inform our beliefs, based on their behaviors and beliefs.”

One of the more interesting studies in this area was a 2013 paper by Jacqueline Woolley et al. involving a fictional character called the Candy Witch. Participating children were told about the Candy Witch, a friendly being who would trade toys for their Halloween candy. But the children had to exercise self-control and not eat all their candy in order to “pay” the Candy Witch for the toys. And their parents had to telephone the witch to arrange for her visit.

The result: most of the children believed the Candy Witch was real, even though they never saw her in person—a belief that persisted in some of the participating children even a year later. “Woolley and her collaborators didn’t frame it in terms of rituals, but she’s subsequently spoken about rituals as a special form of testimony by asking children to refrain from eating all their Halloween candy,” Kapitany said. “It’s piggy-backing on a lot of other structural schemes children have about Christmas.”

In fact, the Candy Witch study is a bit like the infamous marshmallow test, in which young children were left alone in a room with a marshmallow. If they could refrain from eating it for 15 minutes, they would get a second marshmallow when the experimenter returned. The Candy Witch experiment required children to wait two weeks before receiving a present as a reward. “I think we don’t appreciate quite how big the task was that Woolley was asking of these kids,” said Kapitany. “The kind of commitment she asked children to engage in is the kind of commitment which would only be asked if something was real.”

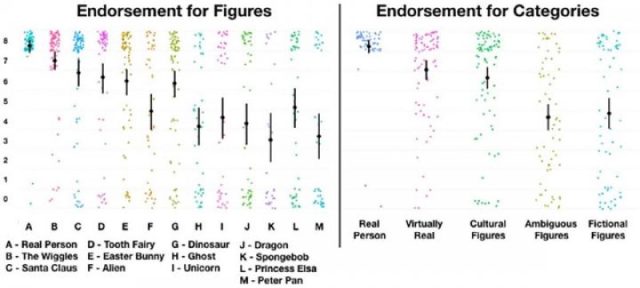

Enlarge / Children’s endorsement scores for individual figures and categories.

Kapitány et al, 2020

Based on those results, Woolley has argued that three factors are required to convince children that a given figure is real: testimony, i.e., being told about the figure; indirect evidence, like Santa filling Christmas stockings, or finding money from the Tooth Fairy under their pillow; and engaging in rituals, like leaving milk and cookies out for Santa, or hunting for the Easter Bunny’s chocolate eggs. Direct evidence, like visiting Santa at the mall, further reduces a child’s natural skepticism. In other words, kids rely on several different lines of evidence as they build their beliefs, some more influential than others—a “hierarchy of endorsement.”

This latest study by Kapitany et al. was intended as “a first attempt to present children with a range of real, cultural, and fictional characters in order to determine whether children build a hierarchy of endorsement,” the authors wrote. They asked 176 Australian children between the ages of two and 11 years old to rate how real they thought 13 different figures were, on a scale of 0 (not real at all) to 8 (very real).

Those figures included Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy, ghosts, dinosaurs, fictional characters (Spongebob Squarepants, Princess Elsa from Frozen), and real figures like the popular Australian children’s music group, The Wiggles. They also had 56 adults participate for comparison. All these figures vary in their degree of “reality.”

The data revealed that most children’s conception of those 13 figures could be categorized into four groups. The Wiggles and dinosaurs ranked highest on the “realness” scale for children (7 points), followed by cultural figures like Santa and the Tooth Fairy (6 points). Ranking lower were ambiguous figures like aliens, dragons and ghosts, and fictional characters like Spongebob Squarepants. For adults and children over seven years old, the 13 figures fell into three groups, with the cultural figures category omitted.

Enlarge / Anthony Field, Emma Watkins, Lachlan Gillespie and Simon Pryce of The Wiggles perform on stage with guitarist Oliver Brian during a live-streaming event at the Sydney Opera House on June 13, 2020 in Sydney, Australia.

Lisa Maree Williams/Getty Images

“The hierarchy is important because not all forms of evidence in our world are equal,” said Kapitany. In the case of testimony, for instance, “I can tell you that pigs fly, but you’re not going to believe that until you have some direct evidence of it.” He believes costly actions, often in the form of rituals, are among the highest forms of evidence in this hierarchy. “You can get belief without rituals, but rituals are particularly useful in providing beliefs,” he said. Per Kapitany, it’s not a coincidence that these things occur in religions or organizations like the military, where ideological conformation is desired.

While the hierarchy of endorsement revealed by the data differed in some ways from their original hypothetical conception, there was still substantial support for much of Kapitany’s ideas. Kapitany has since completed a follow-up study in Europe, and that data replicates the findings, although the paper on that work is still being prepared for publication.

As for future work, Kapitany is keen to conduct experiments similar to Woolley’s Candy Witch project in the lab, rather than relying on correlational data from online surveys. “I would like a more targeted, large-scale study where we could convince children that the oogey-boogey exists, and see if we can get some long-term endorsement and behaviors consistent with that,” he said.

DOI: PLOS ONE, 2020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234142 (About DOIs).