Published April 28, 2022

10 min read

Libraries and rare book collections often carry volumes that feature poisons on their pages, from famous murder mysteries to seminal works on toxicology and forensics. The poisons described in these books are merely words on a page, but some books scattered throughout the world are literally poisonous.

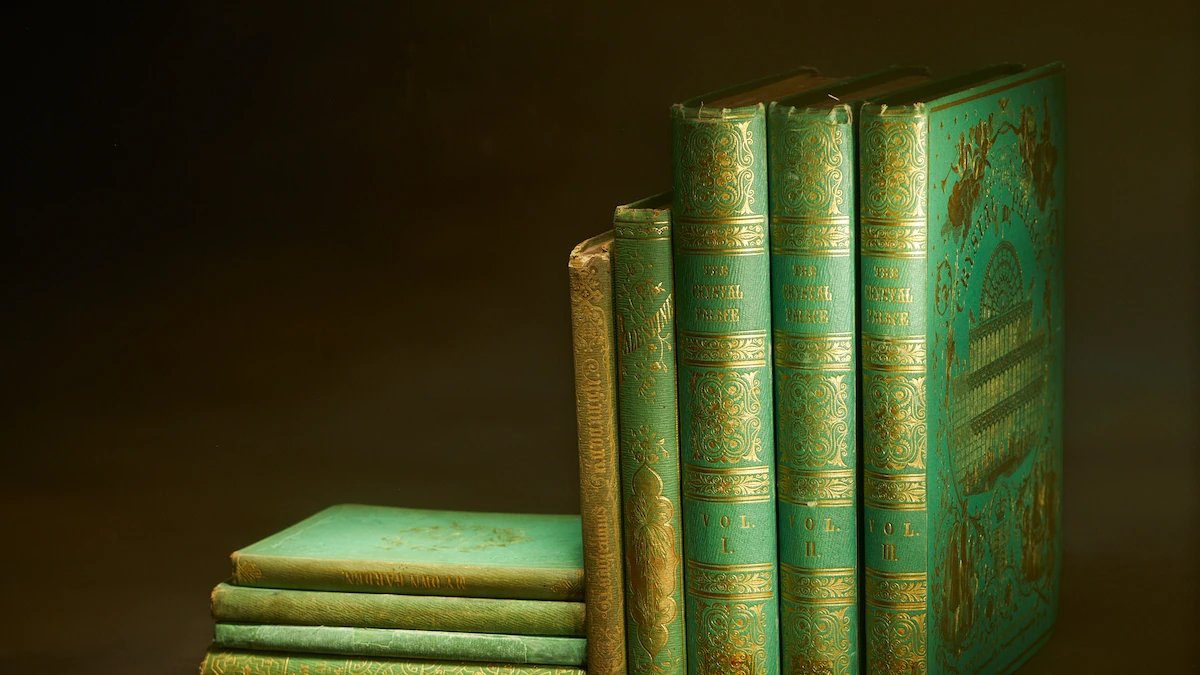

These toxic books, produced in the 19th century, are bound in vivid cloth colored with a notorious pigment known as emerald green that’s laced with arsenic. Many of them are going unnoticed on shelves and in collections. So Melissa Tedone, the lab head for library materials conservation at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Delaware, has launched an effort dubbed the Poison Book Project to locate and catalogue these noxious volumes.

To date, the team has uncovered 88 19th-century books containing emerald green. Seventy of them are covered with vivid green bookcloth, and the rest have the pigment incorporated onto paper labels or decorative features. Tedone even found an emerald green book on sale at a local bookstore, which she purchased.

While these poisonous books would likely cause only minor harm unless someone decided to devour a nearly 200-year-old tome, the alluringly vibrant books are not totally without risk. People who handle them frequently, such as librarians or researchers, may accidentally inhale or ingest particles that contain arsenic, which could make them feel lethargic and light-headed or suffer from diarrhea and stomach cramps. Against the skin, arsenic can cause irritations and lesions. Serious cases of arsenic poisoning can lead to heart failure, lung disease, neurological dysfunction, and—in extreme situations—death.

So just how common are these poison green books? “It’s somewhat hard to predict because our data set is still small, but I would certainly expect there could be thousands of these books around the world,” Tedone says. “Any library that collects mid-19th-century cloth publishers’ bindings is likely to have at least one or two.”

A color to die for

Emerald green, also known as Paris green, Vienna green, and Schweinfurt green, is the product of combining copper acetate with arsenic trioxide, producing copper acetoarsenite. The toxic pigment was commercially developed in 1814 by the Wilhelm Dye and White Lead Company in Schweinfurt, Germany. It was used everywhere, from clothing and wallpaper to fake flowers and paint. To say that Victorian England was bathed in emerald green is an understatement: By 1860 more than 700 tons of the pigment had been produced in the country alone.

Arsenic’s toxicity was known at the time, but the vibrant color was nevertheless popular and cheap to produce. Wallpapers shed toxic green dust that covered food and coated floors, and clothing colored with the pigment irritated the skin and poisoned the wearer. Despite the risks, emerald green was ingrained into Victorian life—a color to literally die for.

While toxic green goods flooded parts of Europe and the United States, another invention transformed the bookmaking industry. Early 19th-century books were handcrafted, leather-bound artisan creations, but the industrial revolution quickly provided a way to mass produce books for a growing population of readers.

Traditional clothing fabric can’t withstand the book binding process, and it isn’t sturdy enough to function as a cover. In the 1820s publisher William Pickering and bookbinder Archibald Leighton developed the first commercially viable process to coat fabric with starch, filling in the gaps of the weave and producing a sturdy material: the first bookcloth.

“It was a game changer,” Tedone says. “Cloth was so much less expensive than leather, which meant you could sell books at different price points.” The process affected more than just the publisher’s bottom line; it changed how books were read. “They were making books accessible to a much wider demographic, catering to people on all levels of the economic spectrum.”

Cloth-bound books took off in the 1840s, and the process of creating bookcloth became a closely guarded secret. “It meant a lot of money to publishers, so unfortunately, there’s not a lot of documentary evidence about bookcloth making,” Tedone says.

What we do know is that book covers could suddenly take on a wide range of hues. Bookmakers produced a colorful array of books with dyes, which are solutions that chemically bond to the substance they’re applied to, and pigments, which are materials that physically coat the substance, like dried mud on a Sunday dress. As such, the era’s most fashionable shade of green pigment could grace the covers of popular books.

The trouble with pigments, though, is that they tend to crack, peel, and flake off over time.

Poison in the library

In the spring of 2019 Tedone received a request from a curatorial fellow at the Winterthur gallery to borrow a book from the library to put on display: Rustic Adornments for Homes and Taste, published in 1857.

“This particular book was very beautiful, bright green with lots of gold stamping. It was very visually stunning, but it was in really bad condition,” Tedone says. “The spine and the boards were falling off, and the sewing had broken, so it needed to be conserved before it could go on exhibit.”

With the beautiful yet broken book under the microscope, Tedone peered at the front board. “There was a black, waxy excretion on the surface, and I was trying to pick it off of the bookcloth with a porcupine quill,” she says. “And then I noticed the colorant in the bookcloth was flaking off really easily around the area where I was working.”

To the untrained eye, this might seem normal for a 162-year-old book, but to Tedone it was surprising. “It didn’t seem like the cloth was dyed,” she says. “It seemed to me that maybe the starch coating on the cloth was mixed with a pigment.”

To learn the identity of the mysterious green pigment, Tedone turned to Rosie Grayburn, head of the museum’s scientific research and analysis laboratory.

Grayburn first studied the sample with an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer, which bombards material with x-rays and measures the energies of emitted photons to determine its chemical composition. This technique can tell you the elements that are present, but not how they are arranged in a molecule. Another technique using a Raman spectrophotometer measures how light from a laser interacts with target molecules, shifting the energy of the laser up or down. Much like each person has unique fingerprints, every molecule has a characteristic Raman spectrum.

The sensitivity of these techniques is key, but equally important is that they are nondestructive. “You shouldn’t be damaging works of art,” Grayburn says.

X-ray fluorescence revealed the presence of both copper and arsenic in the green pigment, a key finding, and the unique fingerprint from Raman spectroscopy positively identified the pigment as the infamous emerald green.

Handling poison literature

The team next used the University of Delaware soil laboratory to measure the amount of arsenic in the cover of Rustic Adornments. They found that the bookcloth contained an average of 1.42 milligrams of arsenic per square centimeter. Without medical care, a lethal dose of arsenic for an adult is roughly 100 milligrams, the mass of several grains of rice.

“What are the implications of having so much arsenic in bookcloth, on your gloves, during treatment? What does that mean for your health and safety?” Grayburn asks.

To answer these question, Tedone and Grayburn reached out to Michael Gladle, the director of environmental health and safety at the University of Delaware. “Arsenic is a heavy metal and does have some toxicity associated with it, principally, either inhalation or ingestion,” he says. The relative risk of emerald green bookcloth “depends on frequency,” Gladle says, and is of primary concern “for those that are in the business of preservation.”

Gladle suggests that anyone handling these tomes should isolate the books and work on them on tabletops with fume hoods to control any arsenic particulates. “People that have access to these old books for research should be wearing gloves and using a designated space to review those books,” he says.

Following Gladle’s recommendations, Winterthur library removed nine green, arsenic-clothed books from circulation and placed them in large sealable polyethylene plastic bags. When handling or conserving afflicted books, they wear nitrile gloves, and afterward they wipe down hard surfaces and wash their hands.

The team then launched a search for more books, travelling 25 miles northeast to the oldest library in America, the Library Company of Philadelphia. There they identified an additional 28 emerald green cloth books. With a larger sample size, they discovered that most books with arsenic-containing emerald green bookcloth were published in the 1850s.

To help others identify the arsenic-clad books and their potential risks, the team designed full-color bookmarks with images of emerald green covers as well as handling and safety precautions. They’ve mailed over 900 of these bookmarks throughout the United States and to 18 other countries, resulting in six other institutions identifying arsenic-laced books in their collections.

Despite the toxicity of arsenic-based emerald green in household goods, wares, and clothing, it was never prohibited. Instead, its use died out naturally, either from its toxic reputation or the color simply falling out of fashion, much like the avocado green appliances in the 1970s.

And the most important message from Tedone, ever the conservator, is to not discard the poison books. “You don’t need to panic and throw them away,” she says. “We just want people to take it seriously.”