When the next coronavirus pandemic hits, scientists plan to already have a vaccine against it, no matter what it is. But how is that possible? Here’s what they’re doing now to develop vaccines against emerging viruses and future variants of COVID-19.

Scientists don’t know when or where the next coronavirus pandemic will emerge. They aren’t sure exactly what virus it will be. But they’re already working to develop a vaccine against it, aiming to have a shot ready to be pulled from a freezer to vaccinate the population before it can spread around the globe.

“We really think that there needs to be more research on emerging diseases and establishing quick platforms or quick solutions that allow us to rapidly respond rather than trying to catch up,” said Prof. Volker Gerdts, CEO and director of VIDO-Intervac at the University of Saskatchewan. His team has just started human trials of its COVID-19 vaccine.

“I mean, even now with a one or two year development of vaccines, which is really, really fast compared to the traditional way, the economic impact still is huge.”

Looking back, researchers say it likely didn’t have to be this way. In theory, it could have been possible to have a vaccine against COVID-19 ready to go when SARS-CoV-2 was identified in February 2020 as the novel coronavirus causing the highly contagious and deadly respiratory illness first reported in Wuhan, China.

Where a new coronavirus could come from

It’s too late for that. But it’s certainly not too late to have vaccines ready for future coronavirus pandemics — something that researchers like Prof. Michael Houghton, director of the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute at the University of Alberta, say we can expect.

We’ve had two SARS coronavirus pandemics in the space of less than 20 years. “So there’s a high probability that we’ll get a third strain of related coronavirus,” Houghton said. “We need to be better prepared right now.”

WATCH | Investigating how the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumped from animals to humans:

Half a year after the first cases of COVID-19 were detected at a wet market in Wuhan, China, investigators with the World Health Organization are now trying to figure out how the virus jumped from animals to humans. 1:53

Such a coronavirus could already exist in animals, such as bats, and then jump to humans, perhaps via other creatures. Alternatively, new-ish coronavirus strains could emerge even sooner from current pandemic.

Already, SARS-CoV-2 is evolving. New variants are emerging with slightly different characteristics, such as higher transmissibility. And some of the vaccines developed against the original strain are not as effective against some of the new variants. As the variant spreads through the global population, the virus is likely to evolve and mutate further.

But how does one develop vaccines against a virus that perhaps doesn’t yet exist? Or if it’s among existing viruses, how do we know which one might be the next to jump to humans and spawn another pandemic? And how does one create, test, and develop a vaccine for such a disease?

Scientists are already working on at least two main strategies:

Cataloguing animal coronaviruses, trying to predict what characteristics make them likely to infect humans, trying to predict what they’ll look like when they jump to humans, and creating a “bank” of many vaccines for that possibility.

Creating a more universal coronavirus vaccine, or pan-coronavirus vaccine, that will protect against multiple different strains.

Strategy 1: Vaccines for every virus

For the first strategy, finding animal coronaviruses is step 1. Bats are a good place to began, as they’re thought to be the origin of both SARS viruses. However, they live in caves that aren’t very accessible and their nighttime flying makes them difficult to catch.

Burton Lim, who is working with Western University researchers to create a bank of bat coronavirus vaccines, should know. The assistant curator of mammalogy at the Royal Ontario Museum, Lim has collected bats in Mexico, the Caribbean and Vietnam.

“I’ve had to crawl on my hands and knees and on my belly to get into caves,” he said. “I’ve crossed over crevices where, you know, I shine my light down into it, and I can’t see the bottom.”

Lim and his colleagues, through their work, have amassed a collection of thousands of bat specimens since the 1960s. Some of them are unique and beautiful when viewed up close.

“Some of them have sort of these weird appendages on their faces that help with their echolocation,” Lim said. “Other bats have these interesting sort of stripes on their faces and on their backs.”

For every bat collected since 1989, tissue samples were taken and frozen — nearly 15,000 from 400 species in 30 countries.

It’s in those tissue samples that Ryan Troyer, an assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at Western University and his team will be fishing for minuscule droplets of coronavirus RNA hiding in a huge pool of genetic material from the bats. (The viruses themselves are killed by preservative chemicals).

They’ll be doing the same kind of hunt in bat feces shared by Lim’s former master’s supervisor, Brock Fenton, a Western University biology professor.

Each coronavirus has a unique “spike” protein that it uses to enter and infect cells.

To test which ones pose the greatest risk of infecting humans, researchers will use the genetic instructions for making each spike protein to create “pseudoviruses” and see which ones can get into animal and human cells.

Making vaccines against the ones that can will be a priority.

Troyer’s colleagues are already working on a vaccine against COVID-19 using replicating viral vector technology. That vaccine carries the gene for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. All the researchers have to do to make vaccines against other coronaviruses is to take the same vector — a harmless “carrier” virus — and replace the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein gene with the spike protein gene from other coronaviruses.

That’s how they plan to create a whole “bank” of vaccines and keep them on hand in a freezer.

“We can store them indefinitely,” said Prof. Stephen Barr, who is also part of Western’s vaccine research team. Researchers say they can quickly produce much more by using each frozen vaccine as a “seed” to grow and manufacture large quantities of that vaccine.

“The idea of the whole thing is really to have vaccines that are as close as possible to a strain which may emerge so that they can be used really rapidly,” Troyer said.

Predicting the next pandemic virus

At VIDO-Intervac, Gerdts’s team is taking that idea one step further. An emerging coronavirus often passes through other animals and becomes somewhat different from the original bat version before infecting humans; Gerdts’s team is trying to replicate this process in the lab.

“We really believe that the science is there to predict what the next pathogen might look like,” said Gerdts. “We can actually force some of these viruses to jump species like you would see in nature… to see if we can develop vaccines that are effective before a new disease emerges, rather than waiting for it to emerge and then try to catch up.”

In the controlled conditions of their containment lab, they plan to grow coronaviruses in cultures of cells from different animals, and in live animals, for generations.

It’s not unlike the process traditionally used to make live, “attenuated” or weakened virus vaccines.

The researchers plan to map the mutations to see which ones occur frequently, in what part of the virus, and how this impacts a pathogen’s ability to get into cells.

“And based on that information, you can then develop vaccines that specifically target these areas.”

Gerdts acknowledged the research could potentially generate a new disease, but said that process is already happening in nature.

“What we’re doing is we’re letting that evolution happen in the high containment lab rather than out on the street,” he said.

His team also plans to make a bank of vaccines to have ready against potential future pandemic viruses.

Strategy 2: One vaccine to rule them all

Instead of filling a vaccine bank with many vaccines against different potential coronaviruses, some researchers are trying to come up with a single vaccine that will work against a variety of different coronaviruses.

One way to do that is to try to generate immunity not just to the spike protein, which is unique for each coronavirus, but to other proteins that look similar in many different coronaviruses.

That’s what Roderick Slavcev and his team at the University of Waterloo and Mediphage Bioceuticals are trying to do.

“That really leads to a much more durable response, not just against variants of SARS, but any other potential future SARS types of viruses,” said Slavcev, an associate professor at the university and founder and chief scientific officer at Mediphage, a Waterloo spin-off company.

The researchers’ DNA vaccine, which is currently undergoing tests in animals, is officially targeted at COVID-19 — it’s just using a different approach from the vaccines already in the market. It will include DNA not just for the spike protein, but also envelope and membrane proteins that form the outside of the virus. It will will generate a “virus-like particle” that includes all three proteins: spike, envelope and membrane. The VLP is similar to a hollow, simplified version of the virus itself.

In theory, that would teach the immune system to recognize them all.

Slavcev thinks one advantage is that even before a future coronavirus emerges, this type of vaccine could offer more protection against new variants of COVID-19 popping up as the current pandemic spreads.

WATCH | The race between COVID-19 vaccines and variants:

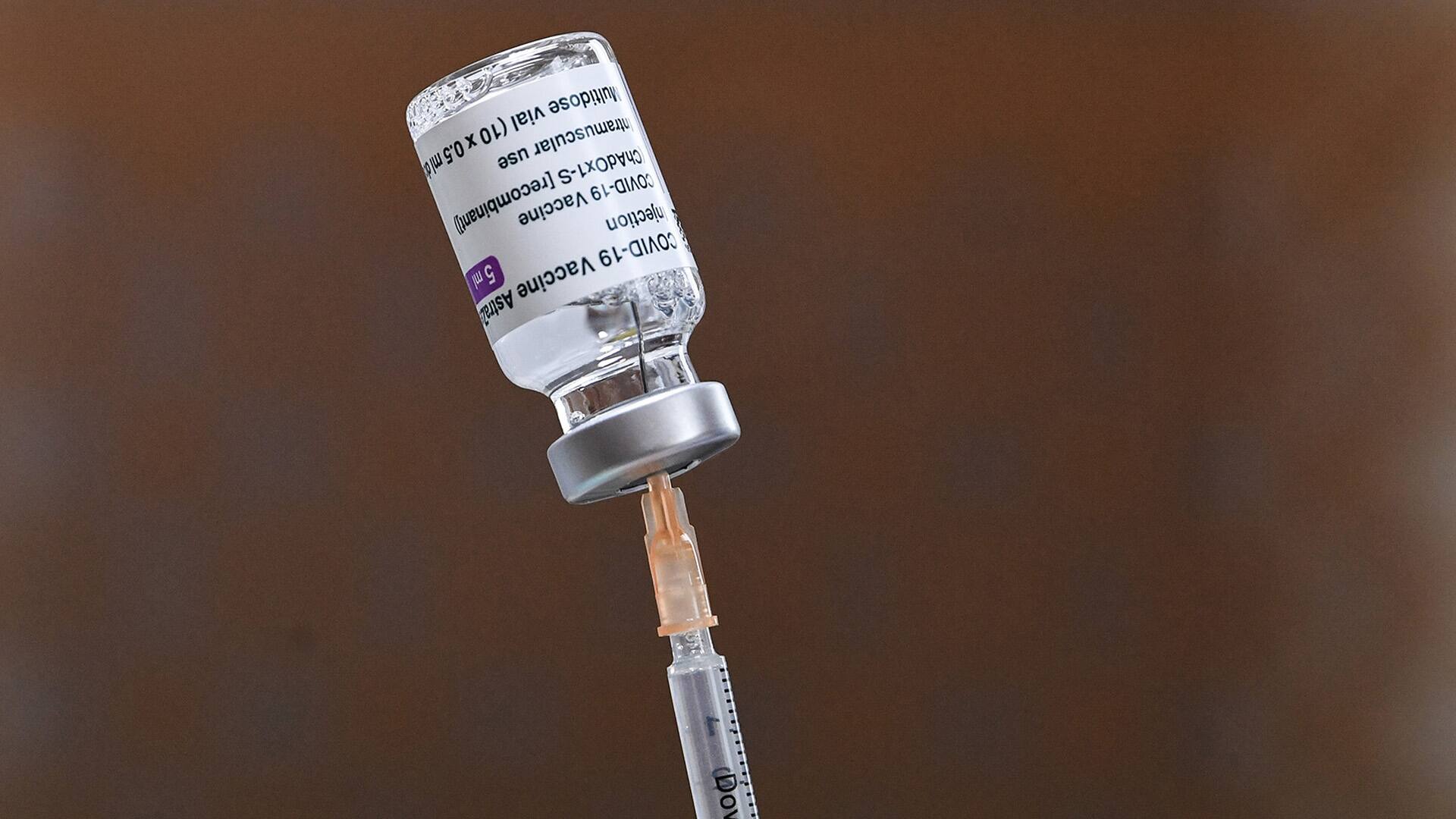

South Africa has halted its rollout of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine after a study showed it offered minimal protection against mild infection from a variant spreading there. While experts say it’s cause for concern, they say vaccines can be reconfigured to protect against mutations. 2:01

One challenge with attempts to make more universal vaccines is that areas that are similar between many viruses may not be as good at triggering the immune system to produce lots of antibodies as, say, the part of the spike protein that binds to a cell.

The University of Alberta’s Houghton said one strategy to compensate involves generating vaccines targeted at two very different variants, and vaccinate a person with both, one after the other. It’s a strategy called “heterologous prime boost.”

The idea is that the body’s immune system would be exposed twice to the similar part of the virus in both variants, boosting the production of antibodies that respond to those parts.

And Houghton says his lab has a small grant to look into that strategy, targeting a part of the spike protein called the C-terminus that is similar in different spike proteins.

But how ready will the vaccines be?

One issue with generating vaccines for pandemics that don’t yet exist is there’s also only so far the testing can go.

Phase 3 clinical trials test effectiveness in real world conditions, so a disease needs to be spreading in the community.

However, Gerdts said it’s possible to do preclinical testing on animals for safety and to measure immune response, and potentially even Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials in humans.

Houghton said those early trials are not that expensive.

WATCH | Canada’s long-term strategy to make vaccine for COVID-19 and beyond:

Canada may not have a vaccine in production yet but it does have a long-term strategy in the works — to develop a made-in-Canada vaccine and the vaccine independence that comes with it. 8:15

One advantage of the more universal vaccines is they’re designed to protect against COVID-19 too, and can go through the entire range of clinical trials.

On the other hand, Troyer said, a more universal vaccine may not necessarily work broadly enough to be effective against the next pandemic virus.

“I think the difficulty of the one size fits all approach — the real barrier to that — is just the diversity of coronaviruses.”

Barr said the two approaches are complementary to some extent, as each might work in circumstances where the other won’t.

He added that evolution will eventually drive coronaviruses to mutate and evade strong protection from any vaccine, including one that works on many different variants.

“And when it does that, then that so-called global vaccine won’t work,” he said. “And so then we’re going to have to go back to the more specific ones that we are working on.”

Researchers also agreed that having small samples of vaccines for future pandemics in the freezer isn’t enough.

Houghton said governments also needs to incentivize companies to make and stockpile larger quantities. He also recommends building up Canada’s manufacturing capability for mRNA and viral vector vaccines. Those are technologies where genes for new viruses and variants can be easily swapped into an existing vaccine platform.

WATCH | The possibilities of mRNA vaccines beyond COVID-19:

The ground-breaking technology used to create the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, mRNA, could also be used to produce vaccines for other diseases including HIV, the flu and even cancer. 5:18

Gerdts said the right kind of manufacturing facilities are also key to be able to quickly make vaccine doses for testing.

All the researchers, who are also working on vaccines for the COVID-19 pandemic, agreed that right now is a good time to start readying for the next pandemic.

“It’s not a question of if another pandemic will occur — it’s when,” said Barr. “And we need to be prepared now so that we can protect ourselves and don’t fall into the same situation as we are in right now.”