On the fifth day of Christmas —

Two studies, published 11 months apart, yield conflicting results.

Jennifer Ouellette

–

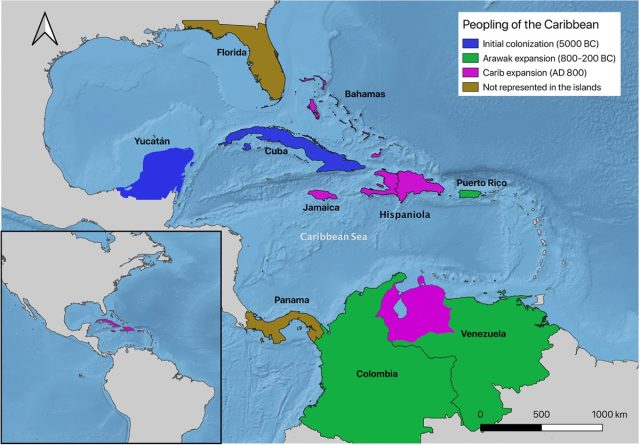

Enlarge / Earlier this year, researchers analyzed the skulls of early Caribbean inhabitants, using 3D facial “landmarks” as a genetic proxy for determining how closely people groups were related to one another. A follow-up study this month added ancient DNA analysis into the mix, with conflicting results.

Ann Ross/North Carolina State University

There’s rarely time to write about every cool science-y story that comes our way. So this year, we’re once again running a special Twelve Days of Christmas series of posts, highlighting one science story that fell through the cracks in 2020, each day from December 25 through January 5. Today: how facial characteristic analysis and DNA analysis, combined with archaeological work, are helping shed light on the history of the Caribbean’s original islanders.

In his accounts of encounters with the inhabitants of the Caribbean Islands in the 15th century, Christopher Columbus made several allusions to Carib raids upon peaceful Arawak villages, including sensational claims of the invaders eating the men and taking the women as wives. “I saw some who had marks of wounds on their bodies and I made signs to them asking what they were,” Columbus wrote in one account from his first voyage, upon arriving on the Bahamian island of Guanahani. “They showed me how people from other islands nearby came there and tried to take them, and how they defended themselves; and I believed and believe that they come Tierra Firme to take them captive.”

Most archaeologists have long dismissed these accounts as myths, but new scientific tools are helping shed light on the truth of the Caribbean’s original islanders. And the conflicting results of two separate studies, published 11 months apart, are raising fresh questions. The results of an analysis of facial characteristics from ancient human skulls from the region seemed to indicate Columbus’ account was accurate, according to a January paper published in Scientific Reports. But a follow-up paper published last week in Nature yields a different picture with its combination of genetic analysis with decades of archaeological research.

Archaeologist William Keegan, curator of Caribbean archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, and a coauthor on both studies, has been studying this region for more than 40 years. Per Keegan, it’s a vast archipelago extending nearly 3,000 miles from the mouth of Orinoco River in northern South America to Florida and the Yucatan, and it includes three major island groupings in the Caribbean Sea: the Lesser Antilles, the Greater Antilles, and the Bahamas.

Enlarge / Cannibalism in Brazil depicted by Theodor de Bly, 1596.

Public domain

According to Keegan, the working hypothesis among archaeologists has long been that the Caribs only arrived in the region shortly before Europeans, and even then were found only in the Windward Islands at the Lesser Antilles, based on decorations found on ancient pottery. It was assumed Caribs had never made it farther north than Guadalupe. He himself ascribed to that view until the facial characteristic analysis showed evidence of a distinct third migratory group—evidence that Carib marauders did indeed invade Jamaica, Hispaniola, and the Bahamas.

Keegan ruefully admitted at the time that he set out to prove Columbus was wrong, but the January findings seemed to prove the famed explorer right. Then came the results of the DNA study, which showed only two distinct migratory groups, once again muddying the waters.

“We have several different notions of what Carib might be,” Keegan told Ars. “We have cultural evidence, we have Columbus’ reports, we have the accounts of French missionaries in the 1700s. Trying to sort through what all these different Caribs are, or whether they’re even just one single cultural group, is what we were hoping that the DNA would help sort out. But as often happens in science, our questions are more subtle than our data.”

“Facial profiling”

Keegan’s co-author Anne Ross had published a study a few years ago on facial characteristics from different populations around and in the Caribbean region, and found that people who lived in Cuba had distinctly different features than those who lived in Hispaniola. “An enduring question has been whether the Lucayans, who settled the Bahamas, came from Cuba or from Hispaniola,” said Keegan.

The question endures in part because it can be challenging to collect sufficient samples of ancient skulls. “Once bones are in the ground, or underwater, for a long period of time, the facial bones are the most fragile and tend to break apart and collapse,” said Keegan. “So it’s difficult to get a complete enough face to do these kinds of measurements. And we’re not out there actively looking for human burials so it’s sort of catch as catch can.”

Fortunately, the National Museum of The Bahamas has a substantial collection of human skeletons, a vital resource for archaeologists like Keegan. The latest skulls came from a 2016 rescue excavation after a Lucayan burial site was disturbed by Hurricane Joaquin and began washing out the side of a sand dune. Despite his profession, “Personally, I don’t think we should be keeping human remains in repositories,” said Keegan. “It’s kind of a sensitive matter. It does affect our ability to do research. But I think humans deserve to have a certain degree of respect no matter when they died. So my goal is eventually to have all the human remains in the collection reburied in an appropriate location.”

Enlarge / A map showing proposed three migration routes for the peopling of the Caribbean.

A.H. Ross et al/Scientific Reports

The intentional modification of facial structure was common practice at the time: namely, the flattening of the forehead, which changes the shape of the back part of the skull. “The parietal bones over your ears become more bulbous and the back of the skull—the occipital—becomes flat,” said Keegan. “And then, of course, the forehead slopes backwards.”

But that type of modification doesn’t affect the characteristics Keegan and Ross examined in their study. “Biological anthropologists have known for years that your facial appearance is affected by your genes,” he said. They have developed a set of specific measurement points to create facial reconstructions of how various peoples from that era looked, and it’s been demonstrated that there are regional differences between a person from Cuba, a person from Hispaniola/The Bahamas, and a person from Puerto Rico—what Keegan jokingly calls “facial profiling.”

After finally being able to study enough skulls, they discovered three separate clusters instead of the expected two: a Cuba cluster, a Puerto Rico/Venezuela/Colombia cluster, and a Hispaniola/Jamaica/Bahamas cluster. That prompted Keegan et al. to reexamine a pottery style known as Meillacoid, found only in Hispaniola, Jamaica, and the Bahamas, which anthropologists had previously thought were a separate migration.

“We found that the pottery style was much more consistent with the way those people called Caribs made pottery than the way people called Arawaks made pottery,” said Keegan. “Those two lines of evidence led us to conclude that [Caribs] actually were in Hispaniola, Jamaica, and the Bahamas when Columbus arrived.”

As for the reports of cannibalism in Columbus’ accounts, hard evidence as to whether this was truly a regular practice is still lacking. “The Caribs in the Lesser Antilles told Europeans that they kill and eat their enemies, but this could be hyperbole,” said Keegan. “We don’t have any skeletal evidence. We’re not finding human bones that are cooked or butchered—at least we haven’t yet.”

DNA finds three’s a crowd

To follow up on those findings, Keegan teamed up with David Reich of Harvard Medical School to see if there was sufficient genetic evidence to support the conclusions from the facial profiling. The DNA study published last week analyzed the genomes of the remains from 263 individuals—the largest such study to date for ancient DNA in the Americas. They collected genetic material from a small, dense part of the bone that protects the inner ear.

The results: Reich’s team found evidence of two major migratory waves in the Caribbean, with two distinct groups—but not a distinct third group, as Keegan had hoped. Rather, the skulls examined in the facial profiling study were part of a subgroup within the main Caribbean group. Keegan thinks this might be the result of the so-called “bottleneck effect,” or “founder effect,” whereby only a small part of a given population moves into a new area, and thus do not carry the full range of the genetic diversity of the parent population with them.

“It’s possible that a smaller group from the larger Caribbean group moved into the Bahamas and therefore they’re slightly distinct from the major Caribbean genetic population,” he said. That’s substantiated by archaeological finds in the region, such as gold objects from Colombia, or jadeite from Guatemala. “We find objects from all over moving throughout the Caribbean,” said Keegan. “It’s a very connected world.” It’s also borne out by a study of male X chromosomes, showing 19 pairs of genetic “cousins” living on different islands, according to Keegan.

Coauthor Harald Ringbauer, a postdoc in Reich’s Harvard Lab, also developed a new technique to estimate past population sizes, based on shared segments, which could prove useful to future ancient DNA studies. The authors estimate that just between 10,000 and 50,000 people inhabited the largest two islands—Hispaniola and Puerto Rico—rather than the million or so inhabitants Columbus reported in his journals.

Enlarge / Some archaeologists pointed to dramatic shifts in Caribbean pottery styles as evidence of new migrations. But genetics show all of the styles were created by one group of people over time. These effigy vessels belong to the Saladoid pottery type, ornate and difficult to shape.

Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland

Meanwhile, Keegan’s research continues. “We did not find genetic evidence for a separate migration,” he said. “But then the question becomes, what do these differences in facial morphology mean? The Ceramic Age had essentially one signature that included everyone from Western Venezuela to Hispaniola. So we could not rule out the movement of people from Western Venezuela (our ‘Caribs’). Also, there were no samples from Jamaica and only two from Haiti, so there is not sufficient genetic evidence to reject the separate migration hypothesis.”

So what comes next? There’s more facial profiling to be done, and Keegan and his geneticist collaborators will be expanding their analysis to include ancient DNA samples from Jamaica, Haiti, the Lesser Antilles, and more of coastal Venezuela, to see if that changes the findings. The team is also wrapping a study involving mitochondrial DNA, and preliminary results indicate at least three different mitochondrial lineages moving into the Bahamas, even though from a genome perspective it’s all one population.

One other intriguing finding from the DNA analysis concerned the evolution of Caribbean pottery styles over 2,000 years, as the Archaic Age gave way to the Ceramic Age in the region. There are five distinct marked shifts in style noted by archaeologists: red pottery decorated with white painted designs, for example; pots with tiny dots or incisions; or more ornate styles of pottery with sculpted animal faces. Some archaeologists have viewed this as evidence for fresh migrations to the Caribbean, but the DNA analysis suggests that all the styles in fact were developed by descendants of the same people who arrived in the Caribbean some 2,500 years ago.

“It confirms what we expect, but as a social scientist, it just goes to show that genetics can’t give us a complete picture of the people who carry those genes,” said Keegan. “Genes may be discrete units that we can measure, but genomes are created by cultures.”

DOI: Scientific Reports, 2020. 10.1038/s41598-019-56929-3 (About DOIs).

DOI: Nature, 2020. 10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2 (About DOIs).