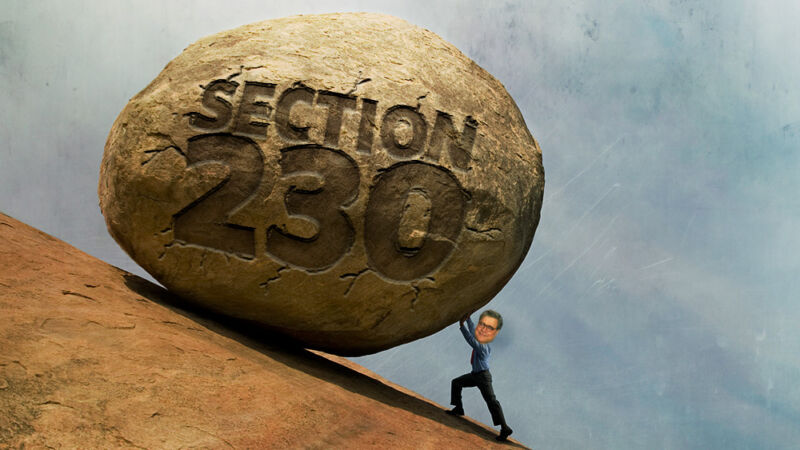

status quo’nt —

DOJ recommendation is an 8,000 word wish list—only Congress can change the law.

Kate Cox

–

The Department of Justice today released a set of proposals calling for sweeping reform to the law that grants immunity to apps and websites for the content users post or share to them, following months of political rhetoric about the supposed suppression of conservative speech online.

The proposal outlines recommended changes to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. “The time is ripe to realign the scope of Section 230 with the realities of the modern internet,” the DOJ wrote. “We must ensure that the internet is both an open and safe space for our society.”

The report (PDF) stems from a nearly year-long investigation into Big Tech that began in the department’s Antitrust Division last July. The DOJ said at the time that the probe would “consider the widespread concerns that consumers, businesses, and entrepreneurs have expressed about search, social media, and some retail services online.” The agency did not name names, but Amazon, Facebook, and Google were widely considered to be on the list.

“Section 230” has become a rallying cry for politicians of both parties who feel that the status quo of social media isn’t working. Many aspects of the modern social media landscape are, in fact, not quite working, and there is indeed room for improvement in the field. Most often, though, complaints about speech on the Internet woefully misunderstand what Section 230 is, says, and does.

The law, at its core, means that websites and apps aren’t responsible if a user posts something defamatory or unlawful to the service—if you commit libel in a Tweet, you, not Twitter, are responsible for the content of your message. But the law does not make any requirements about content, including about neutrality. Under existing law, platforms are free to host the kind of content they wish and to moderate the kind of content they wish. (Ars’ own Timothy Lee gave a more in-depth explanation of the law earlier this month.)

The DOJ appears to want to thread the needle between extremes. “Many have called for an outright repeal of the statute in light of the changed technological landscape and growing online harms,” it writes. “Others, meanwhile, have insisted that Section 230 be left alone and claimed that any reform will crumble the tech industry. Based on our analysis and external engagement, the Department believes there is productive middle ground and has identified a set of measured, yet concrete proposals that address many of the concerns raised about Section 230.”

So what’s in that middle ground?

The proposal

The report basically splits up the key findings into a few big buckets. Its primary group of proposals involves creating new incentives for platforms to address “illicit content” while preserving “immunity for defamation.”

Those incentives fall into three more categories. Primarily, the DOJ proposes “denying section 230 immunity to truly bad actors.” Bad actors, in the proposal, are considered those who “purposefully facilitate criminal activity or material.” The report acknowledges that this kind of carve-out could be ripe for abuse in the form of “frivolous litigation.” To ameliorate that, the proposal would limit the “bad Samaritan” carve-out to violations of federal criminal law only and subject claims to a heightened scrutiny.

The carve-out also applies to “actors who purposefully blind themselves and law enforcement to illicit material.” In other words: you can’t just not have a reporting mechanism for bad stuff and then claim you had no idea bad stuff existed on your platform. Users should be required specifically to have access to a mechanism “for users to alert platforms of illegal activity,” which under current law is permitted but not required.

The DOJ also goes a step further and suggests that all services should have to log and keep such reports for sharing with law enforcement in order to maintain their existing level of rights. “In order to enjoy the broad immunity” of Section 230, the DOJ then proposes, a platform “must maintain the ability to assist government authorities to obtain content (i.e., evidence)” in a “comprehensible, readable, and usable format.”

The proposal also directly challenges the ability for platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to moderate content that may be vile and harmful but not actively unlawful. Under current law, platforms are allowed to moderate anything they find “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable.” Both platforms, for example, have restrictions of one kind or another on obvious hate speech and threats. This, the DOJ suggests, is too vague, and the “otherwise objectionable” language should be removed from the law.

So now what?

The DOJ’s list of takeaways and recommendations are exactly that—recommendations. Congress passed the Communications Decency Act in 1996, and only Congress can amend it.

There is some interest in Congress for amending current law. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) told Recode in an interview last year that she didn’t think major tech firms were treating the law “with the respect that they should” and added, “I think that could be a question mark and in jeopardy.”

On the Senate side, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) almost exactly one year ago introduced a bill that would revoke Section 230 “immunity” for large tech firms “unless they submit to an external audit that proves by clear and convincing evidence that their algorithms and content-removal practices are politically neutral.”

Hawley was back today, introducing another bill related to Section 230. The new one would specifically allow individuals to sue large social media firms “who act in bad faith by selectively censoring political speech and hiding content created by their competitors.”

Both in 2019 and today, Hawley explicitly cited the supposed silencing of conservative speech as his motivation for the bills, claiming users have no recourse and adding, “Congress should act to ensure bad actors are not given a free pass to censor and silence their opponents.”

If the DOJ proposals were to become law, they would almost certainly face immediate legal challenges. Congress, however, was largely in partisan gridlock even before the novel coronavirus crisis struck. Now, with a pandemic still ripping through the nation and the 2020 election less than five months away, action on a wide array of issues seems even harder to come by. Even if a member of the House or Senate does craft and introduce a bill incorporating all of the DOJ recommendations, it seems unlikely to go anywhere before the current Congress ends in January.