That’s no planet —

Unsuccessful at finding planet X? Substitute with undetectable black hole.

Chris Lee

–

Planet X has a long and storied history of non-existence. For about 130 years, astronomers have debated the existence of an additional planet or planets to explain discrepancies in the orbits of the known planets (mainly Neptune and Uranus). Later, the list of discrepancies was expanded to cover trans-Neptunian objects. But none of the Planet X candidates discovered, including Pluto, have the mass or location to explain observations.

Primordial black holes have now been proposed as the latest planet X (or planet 9, since Pluto was demoted).

Orbital weirdness

Planet X’s origin starts with the discovery of Neptune. Neptune was not found by accident: observations of oddities in the orbit of Uranus were used to calculate the location of Neptune, and it was subsequently found.

That is a game that can be played more than once. Astronomers then noted that Uranus and Neptune’s orbits could be better explained by the existence of another large planet. Follow-up observations have found numerous objects: Pluto and Charon, Sedna, and Eris to name a few. None of these far-flung bodies is large enough to be planet X. But some of their orbits may also suggest a new planet is needed.

Some trans-Neptunian objects have very weird orbits. Many are clustered and have highly elliptical orbits, and there is a sub-group that orbits well out of the plane in which the planets orbit. That’s unusual, since the action of gravity and the nature of the disc that formed the planets typically keeps everything close to the same orbital plane. Finding highly inclined orbits suggests that something is pulling the objects back out of the plane.

A planet that is large and far enough from the Sun might explain these orbits. Indeed, researchers have calculated a range of different planet masses and orbits that may account of the behavior of objects like Sedna.

By happy coincidence, the required masses and distances correspond to an observed gravitational lensing anomaly—an excess of events where the gravitational influence of an unseen object distorted the light from distant stars. That is, there is mass out there, and it is unseen. Could this be a new planet?

A series of unlikely events

So, there seems to be mass, but where did it come from? The planet would have to be something like 300-1,000AU from the Sun (for reference, Neptune’s orbit is just 30AU), where there is very little rock or gas. Simply put, a planet could not form out there. One possibility is that the planet formed closer to the Sun and was ping-ponged out there by interactions with one or more of the gas giants. However, to stabilize at a distant orbit, a passing star (or something similar) is required, which seems unlikely. The remaining option is that our Sun captured a freely wandering planet.

But wanderers need to have been expelled from their own solar system, meaning that most of them are moving at a fair clip. Hence, the chance of capturing such a planet in the required orbit is low, although not impossible.

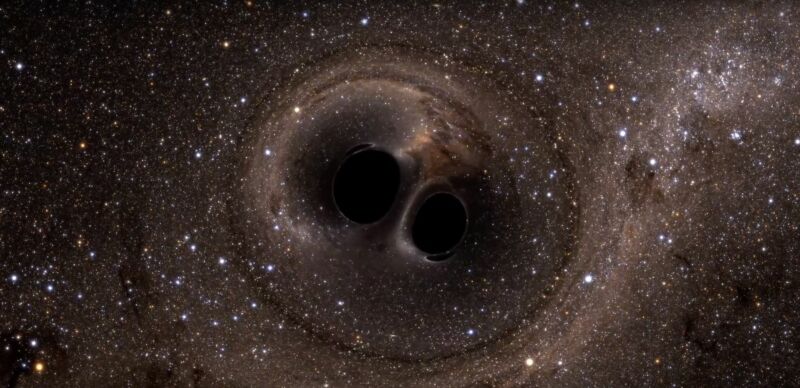

The new paper argues that, if we are looking at a low-probability event, why not a primordial black hole? Primordial black holes might have formed shortly after the Big Bang. And, unlike black holes formed from collapsing stars, they could have masses ranging from tiny (10µg) on upwards. That means there should be a few with the right mass range. How many is a matter of speculation.

Drawn in by the idea, the researchers started rolling d20s: they set primordial black holes to an arbitrary low number and then concluded that capturing a black hole is about as likely as capturing a wandering planet.

In for a penny, in for a pound

If planet X were indeed a black hole, how would we know? The researchers argue that dark-matter annihilation is the thing to search for.

No one knows if primordial black holes exist. No one knows if dark matter annihilates, and if it does, there is no certainty that it does so in a way that is detectable—dark matter could annihilate with itself to create other forms of dark matter, leaving us, well, in the dark. Thus, a speculative product of the early Universe cannot be directly detected unless another speculative process happens to occur in the right manner. In which case, it is possible to confirm if a primordial black hole is part of our solar system family.

Underlying the speculation is an interesting coincidence: unexplained gravitational lensing events that happen to be the right mass and distance to explain some very odd orbits of trans-Neptunian objects. That coincidence feels like it cries out for a single explanation, which is what the researchers are trying to do. That makes their house of cards useful.

Physical Review Letters, 2020, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.051103 (About DOIs)