Future of the human race —

Q&A: Walter Isaacson’s account is a thrilling tale of scientific discovery.

Megan Molteni, Wired.com

–

3d render of DNA spirals.

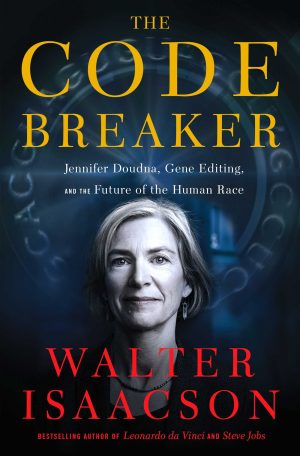

According to Walter Isaacson, three great technology revolutions have shaped the modern world, based on three fundamental kernels of human existence: the atom, the bit, and the gene. Having explored the physics revolution through the eyes of Einstein and the digital revolution via Apple’s supreme leader, Steve Jobs, the best-selling biographer thought it was time to turn to DNA. It’s no surprise then, that he chose Jennifer Doudna, the co-discoverer of the CRISPR gene-editing technology, to carry the tale of how the human species seized control of its own evolutionary destiny.

Isaacson’s latest book, The Code Breaker, breathlessly follows Doudna from a childhood spent trekking through the wilds of Hawaii to her pioneering work harnessing a bacterial defense system to rewrite the code of life—and the bitter patent battle that ensued—and ultimately winning the ultimate credit, the Nobel Prize. Based on more than five years of reporting from the front lines of the DNA-hacking wars, the book is an immersive deep dive into the fascinating science of gene editing and the personal dramas playing out behind the discoveries. Even if you think you know the story of CRISPR, you don’t know it the way Isaacson does.

He spoke to WIRED from his home in New Orleans, where he is now a professor of history at Tulane University. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WIRED: The biotechnology revolution didn’t start with CRISPR or with Doudna. So why her?

Walter Isaacson: Jennifer Doudna’s journey begins in sixth grade, when her dad leaves The Double Helix, by James Watson, on her bed and she realizes it’s actually a detective story. That’s what makes her want to be a scientist. And even after her guidance counselor tells her that girls don’t do science, she persisted. Then she helped figure out the structure of a type of RNA that helps answer one of the biggest questions of all: how did life begin on this planet? And then her RNA studies lead her to CRISPR and the discovery that it can be a tool for editing genes, the magnitude of which leads her to gathering scientists to work through the moral issues of how such a discovery should be used.

My dad gave me The Double Helix when I was in middle school, too. And even though I’ve always been interested in biochemistry, I always regretted that I didn’t pursue it beyond a few courses in college. There’s joy in understanding how something works, especially when that something is ourselves. So while there are all sorts of wonderful characters who could have been the focus of this book, Doudna’s life journey just seemed like it would be a compelling narrative thread through this longer history of scientists striving to understand what makes us human.

You don’t shy away from setting up Doudna’s battle with the Broad Institute over CRISPRr credit as a contemporary parallel to Rosalind Franklin’s own struggle to be recognized for her contributions to discovering the structure of DNA. Was that intentional?

What Doudna has done is unlock the mysteries of life with the same mindset as Rosalind Franklin, which is that the structure of a molecule is the clue you need as a detective to figure out how it’s really going to work. When Doudna and Charpentier won the Nobel Prize, a little vision flickered into my mind of Franklin with a tight but satisfied smile on her face.

So, you start writing about Jennifer Doudna, and next thing you know, she wins the Nobel Prize. Coincidence?

Despite what people think about rigged election systems, I don’t have the ability to hack into the voting process of the Swedish Academy. I thought it was too early for CRISPR. I mean, it had only been eight years since Doudna and Charpentier’s landmark paper. But on the morning that the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was due to be announced, I still set my alarm for 4 am so I could listen to the live feed. And when I heard the announcement I let out a holler. The funny thing is, Doudna actually slept through the phone calls from Stockholm. When I talked to her a few hours later, she told me she’d only learned about her win after the fact, from a reporter calling to get her comments.

That moment, in many ways, represented the culmination of a years-long clash over who deserves credit for turning CRISPR from a biological curiosity to one of the most powerful technologies ever invented. What was it like to try to capture that?

Everyone I spoke to was very generous. Feng Zhang, who is the principal competitor for patents and prizes, is one of the most charming, open, and interesting people you’ll ever meet. I was a little worried when I met him, because I was writing about people who had been his rivals, but he couldn’t have been nicer.

And so I think that access helped me show that science is a real human endeavor that often involves a lot of competition—for patents, for prizes, and for recognition. Competition is a good thing. It spurs us on. That was true of the competition between Intel and Texas Instruments in developing the microchip. And it was true with CRISPR. But what’s also true is that when COVID hit, all these scientists put aside the race for patents and turned their attention toward fighting the coronavirus and putting their discoveries quickly into the public domain for anyone joined in that fight to use.

So my hope for the book is that it shows the mix of competition and cooperation that is at the heart of science. And the fact that even though these are real humans with egos and ambitions, they—more than most people—realize, correctly, that they’re a part of a noble endeavor that has a higher purpose. I hope everyone in the book comes across as a hero in their own way, because they are.

You were in the middle of reporting this book when something seismic happened in the world of CRISPR. In 2018, a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui revealed he had not only edited human embryos but started pregnancies with them, leading to the birth of twin girls. How did that affect the trajectory of the story you were trying to tell?

That really became a crucial turning point in the narrative. Because now all these scientists were forced to wrestle with the moral implications of what they’d helped create. But then things changed again when the coronavirus struck. I wound up working on the book for another year to watch the players as they took on this pandemic. And that actually caused my own thinking about CRISPR to evolve.

How so?

I think I felt a visceral resistance at times to the notion that we could edit the human genome, especially in ways that would be inheritable. But that changed both for me and for Doudna as we met more and more people who are themselves afflicted by horrible genetic problems or who have children who are suffering from them. And when our species got slammed by a deadly virus, it made me more open to the idea that we should use whatever talents we have in order to thrive and be healthy. So I’m now even more open to gene editing done for medical purposes, whether that’s sickle cell anemia, or Huntington’s, or Tay-Sachs, or even to increase our resistance to viruses and other pathogens and to cancer.

SIMON AND SCHUSTER

I still have worries. One is I don’t want gene editing to be something only the rich can afford and it leads to encoding inequalities into our societies. And, secondly, I want to make sure we don’t reduce the wonderful diversity that exists within the human species.

Do you have any ideas for how to do that?

I spend the last few chapters of my book wrestling with that question. And I hope not to preach, but to allow the reader to go hand in hand with me and Jennifer Doudna and figure out on their own what their hopes and fears are about this so-called brave new world we’re all stepping into together. I once had a mentor say there are two types of people who come out of Louisiana: preachers and storytellers. He said, “For heaven’s sake, be a storyteller, because the world’s got too many preachers.”

So by telling the tale of CRISPR in all its scientific triumphs and rivalries and excitement, I hope to turn people on to the science. But I also want to make them more qualified to wrestle with one of the most important questions we’re going to face as a society over the next couple of decades: when we can program molecules the way we program microchips, what is it we want to do with this fire that we’ve snatched from the gods?

This story first appeared on wired.com.